Using Bayes' Law to conceptualize political beliefs

Be conscious of your Priors, Likelihood, and Your Loss Function

Bayes law has long been used in Artificial Intelligence research to formalize how beliefs can be formally modeled as more informatiom is added to update a model. It also works surprising well to conceptualize political beliefs. Why do conservatives cling to tradition, postmodernists rip up every story, libertarians treat freedom like gravity, Marxists see class struggle everywhere, and centrists try to balance it all?

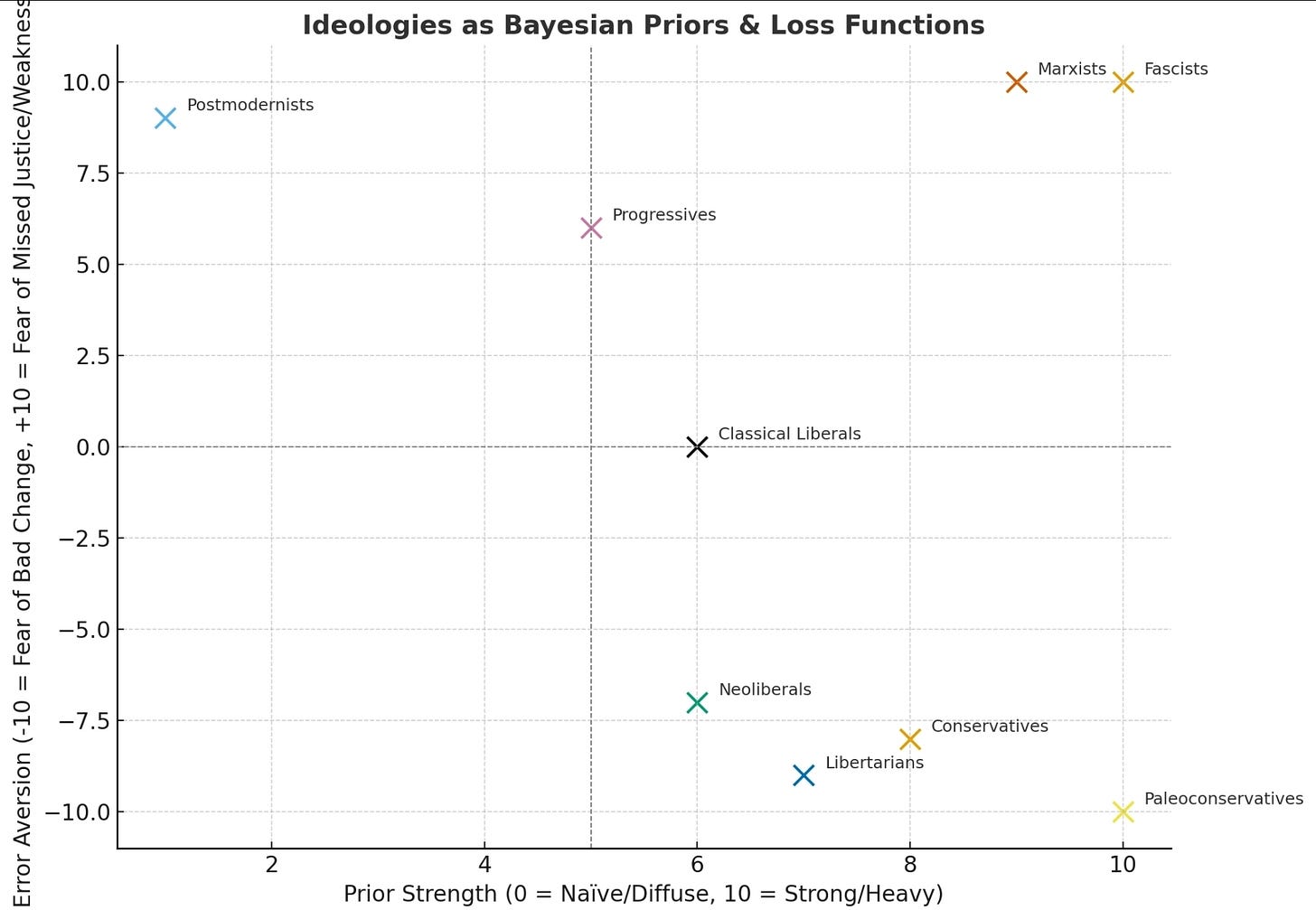

It’s not that one side is smart and another blind. It’s that each group is running the world through a different Bayesian brain, a mental machine that starts with certain beliefs, trusts certain kinds of evidence, and fears particular mistakes more than anything else.

Once you see politics this way, the culture wars stop looking like screaming matches and start looking like competing algorithms.

The Bayesian Game

Think of life as a giant game of guess-and-update.

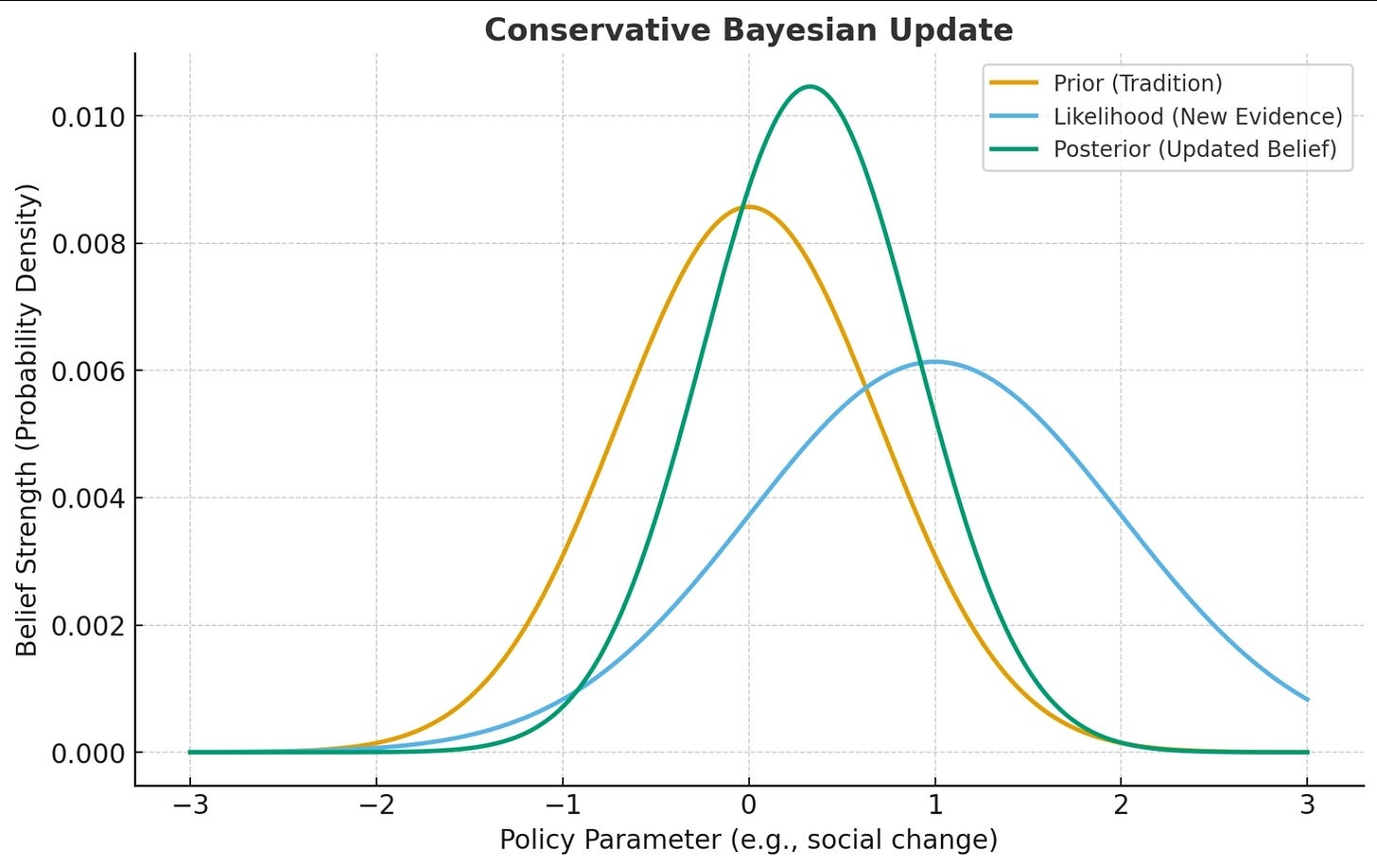

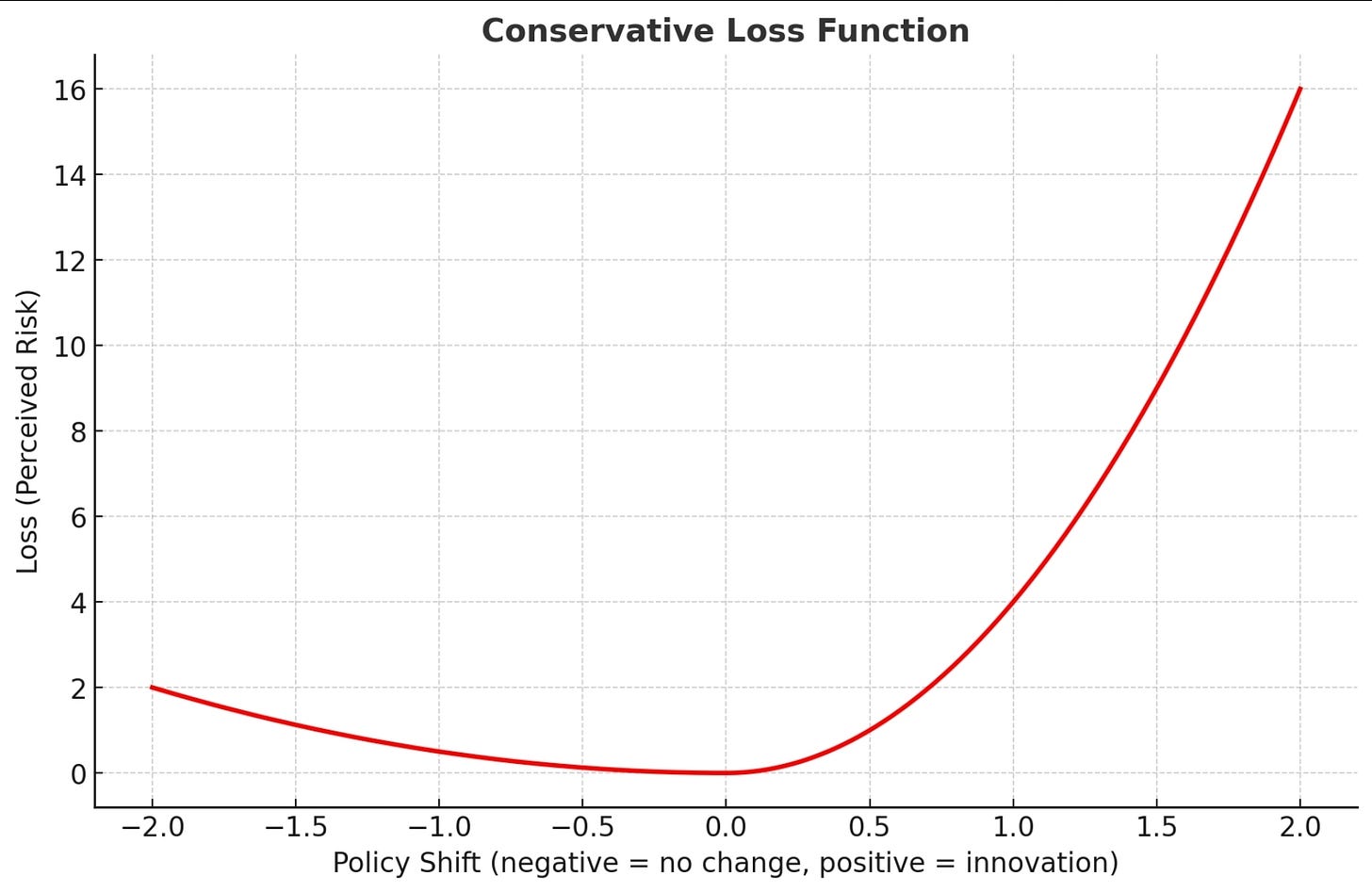

Your prior is your starting belief, your gut feeling based on history or intuition. Your likelihood is how much you trust new evidence. Your loss function is the kind of mistake you most want to avoid. Some fear changing too fast and wrecking everything. Others fear not changing fast enough and letting injustice linger.

Those three dials, prior, likelihood, and loss, explain almost everything about ideological conflict.

Conservatives

Conservatives begin with a strong prior: tradition exists for a reason. They only trust evidence that proves itself over the long haul. What they fear most is a bad innovation that breaks civilization. Their failure mode is ossification, where they cling so tightly to tradition that they ignore real and necessary change.

Postmodernists

Postmodernists start with a flat or diffuse prior: every story is suspect, every “truth” is entangled with power. They trust lived experiences, especially from the marginalized. They fear ignoring oppression. Their failure mode is chaos and nihilism: if all narratives are questioned and nothing sticks, then no shared truth remains.

Neoliberals

Neoliberals begin with a prior that markets usually work. They put faith in GDP, growth rates, and economic data. Their fear is blocking efficiency. Their failure mode is blindness to inequality and social decay, trusting markets even as communities fray.

Paleoconservatives

Paleoconservatives treat tradition as sacred. Civilization is fragile, and new experiments are almost always dangerous. They only count evidence that has lasted centuries. Their fear is collapse through innovation. Their failure mode is freezing in place, unable to adapt when the world changes around them.

Libertarians

Libertarians assume liberty is the natural baseline. They don’t trust centralized plans, only local knowledge and decentralized choices. They fear state coercion more than anything else. Their failure mode is blindness to collective risks, climate change, pandemics, monopolies, that individual choice alone can’t solve.

Marxists

Marxists set their prior on class struggle as the engine of history. Their likelihood function is rigged: every fact, even reforms, becomes proof of capitalism’s contradictions. They fear missing the revolution. Their failure mode is a self-sealing belief system where no evidence can ever disconfirm the theory.

Progressives

Progressives assume society can bend toward justice. They trust both science and the stories of those who suffer. Their fear is failing the marginalized. Their failure mode is complacency, assuming history automatically improves when in fact it can stall or backslide.

Classical Liberals

Classical liberals begin with individual rights, free speech, and rule of law as their prior. They trust open debate and empirical evidence. Their fear is balanced: both tyranny and chaos are to be avoided. Their failure mode is naivety—believing rational debate will always overcome tribalism and passion, when often it doesn’t.

Fascists

Fascists lock their prior on nation, blood, and destiny. They only accept evidence that glorifies the tribe. They fear weakness more than injustice. Their failure mode is posterior collapse: evidence stops mattering entirely, and authoritarian disaster follows.

Centrists

Centrists set their prior on balance itself. They assume the truth usually lies somewhere in the middle. They trust polling data, compromise, and incremental results. Their fear is polarization, where extremes tear the system apart. Their failure mode is mushy indecision—splitting the difference even when one side has stronger evidence.

Why We Talk Past Each Other

When people argue politics, they aren’t just fighting over facts. They are operating with different priors, different rules for evidence, and different fears about mistakes.

That’s why shouting facts rarely changes minds. You’re trying to update someone else’s model with your rules, not theirs.

Failure Modes and Blind Spots

Every ideology has a breaking point. Conservatives risk stagnation. Postmodernists risk nihilism. Neoliberals risk inequality. Paleoconservatives risk brittleness. Libertarians risk ignoring collective threats. Marxists risk closed dogma. Progressives risk complacency. Classical liberals risk naivety. Fascists risk collapse. Centrists risk paralysis.

Once you know these blind spots, you can see where your own worldview is vulnerable.

What’s Your Failure Mode?

So here’s the final test.

What’s your prior? Do you lean on tradition, liberty, equality, balance, or something else?

What kind of evidence do you actually trust? Numbers, narratives, or the weight of history?

What mistake terrifies you most—changing too fast and breaking things, or changing too slowly and letting injustice continue?

And what’s your failure mode? If you push your worldview too far, where does it fail?